Welcome to the AZ Coyotes Insider newsletter. I generally publish stories four to six times per week. By subscribing, you’ll be supporting independent, accountable journalism. Subscribe now so you won’t miss a story.

When Richard Burke chartered a plane during the 1996 NHL All-Star break to fly the Winnipeg Jets players, their wives, their girlfriends and some kids down to Phoenix, he figured he had an easy sell. The January temperatures in Winnipeg had been hovering somewhere between five and 30 degrees below zero.

“I will never forget when they opened the door for the players and wives to get out when we landed,” said Burke, who had bought the team from Barry Shenkarow the previous October with the original intention of moving it to Minneapolis. “The sun generally doesn't come out a lot in Winnipeg in the winter time and there was a traffic jam at the top of the steps. Each of the players would stop and stare out at blue skies, sunshine and 70 some odd degrees. Somebody would literally have to make them walk down the steps so the next player could come up and do the same thing.”

The Jets were there for a tour of what would eventually become their new home. They met fans and dignitaries, they toured schools for their kids, they toured America West Arena with its odd configuration, and they got an early introduction to the dramatic differences between the desert and the frozen tundra.

“Somebody gave me a cactus in a pot,” former captain Shane Doan said. “I’m a 19-year-old kid and I’m thinking. ‘I can barely take care of myself,’ and then I learned that you really don’t have to do anything to take care of a cactus.”

Spines aside, cacti were the least of the new threats.

“We were staying at the Princess (in Scottsdale) in this beautiful villa with one of our kids still in a crib,” forward Kris King said. “We came in from a walk one day on the property and there was a scorpion in our room. I phoned the front desk and I said, ‘I’m not trying to be unappreciative because we really like where we're staying, but there's a scorpion in our room.’

“They sent four people over to deal with it. They packed us up and moved us out of the villa and into a really nice room. My wife felt so bad. She said, ‘Well, it's just a little scorpion’ and they said, ‘Oh, no, those are the bad ones.’”

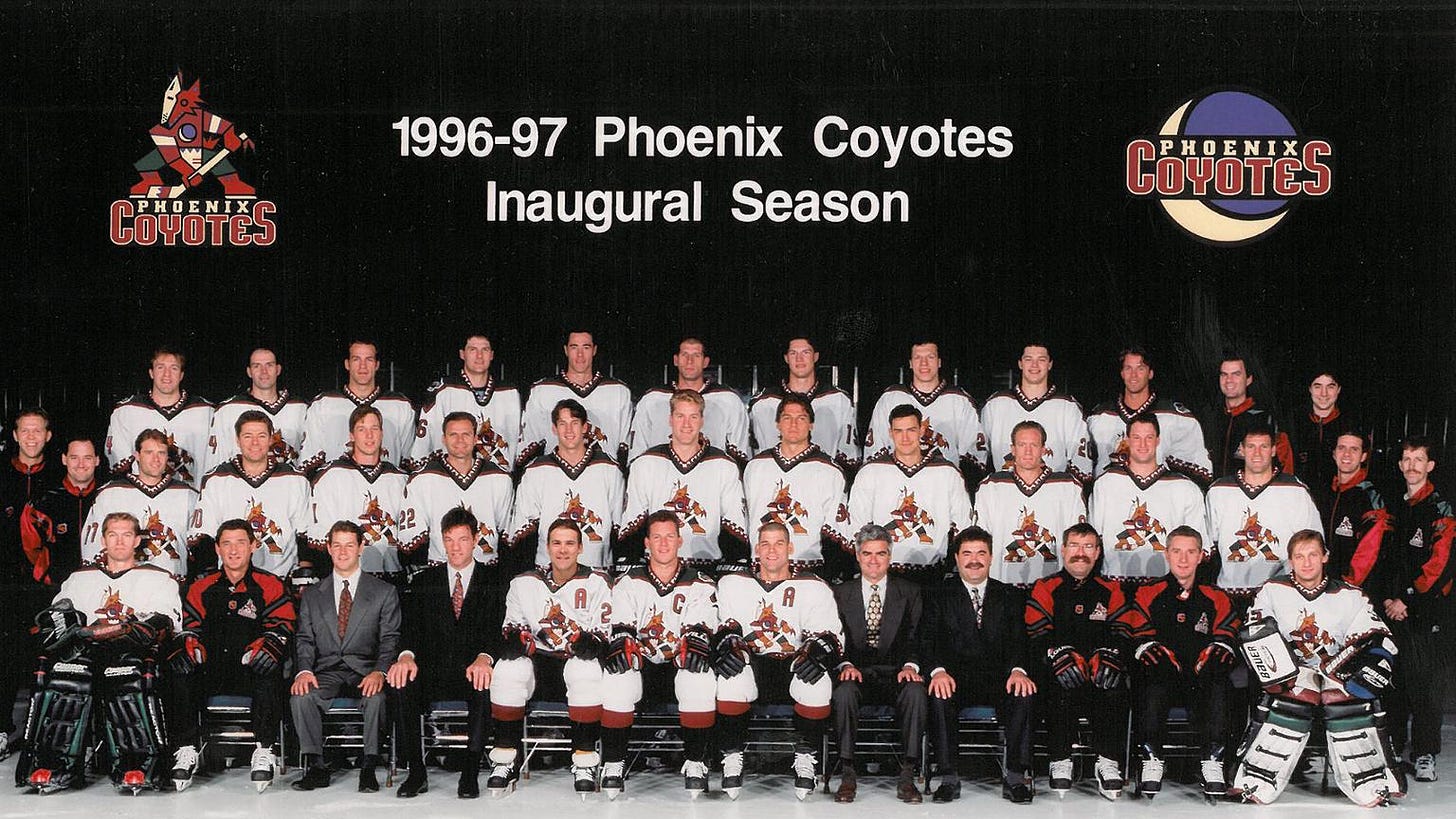

Scorpions and rattlesnakes — like the one goalie Darcy Wakaluk found in his pool filter — aren’t the only challenges the Coyotes have faced in the Valley. Among the earliest hurdles were: selling the game to a market with a spotty understanding of the sport, escaping the first round of the playoffs, and building a new arena when the economics of America West no longer meshed with rising payrolls. Later came the ill-advised move to Glendale, the incessant talk of relocation, two decades of ownership instability, awful draft-lottery luck, massive financial losses and two lengthy playoff droughts.

The Coyotes have been the butt of jokes, they have been targets for derision, and when it comes to the on-ice product, they are running neck and neck with the Florida Panthers as the least successful franchise in the NHL’s Sunbelt experiment. In spite of all that, the Coyotes celebrated their 25-year anniversary in the Valley on July 1. And with the NHL’s new national TV deal on the horizon, and with sports gambling now legal in Arizona and owner Alex Meruelo holding one of precious few licenses, it’s probably fair to say that the Coyotes are here to stay.

“I’m excited that we have reached this milestone and I think the best is yet to come,” commissioner Gary Bettman said. “I think the strength of the franchise, and in particular the ownership as well as its commitment, has never been greater. The fan base has never been as large or as enthusiastic. The vital signs are all good and the opportunities moving forward remain great, which is why I feel very good about the future of this franchise.”

Relocation revisited

Rich Nairn landed his dream job when he joined the Winnipeg Jets in 1993 and was promoted to director of media relations in 1995. Although he was born in Regina, Saskatchewan, he had moved to Winnipeg when he was 3, his family and friends were all there and hockey was a passion.

Almost as soon as he joined the franchise, however, rumors of instability and a possible relocation began swirling.

“It was a bizarre three years,” said Nairn, now the Coyotes executive vice president of communications and broadcasting. “Three years before we left, we were told we were leaving, but two years before we left, we were told that there were projects in the works to build a new arena and we were staying. And then the last year before we moved, it wasn’t happening and we had to move. We were basically a lame duck.

“I was devastated because it was my hometown and my dad lived there, my extended family and friends lived there, my life was there. The fans were devastated, too, because, much like the Green Bay Packers, all you had was hockey and the fans were incredibly loyal and supportive. It was hard to accept and understand. Winnipeg gets a bad rap for players not wanting to play there but the reality is the players loved playing there. They were treated like gods. We had their support and we had the Whiteouts. The reason we left was not due to fan support. We were a small-market team in a building that was built in the 50s. It didn’t have any luxury suites, club seats and naming rights weren't even being considered in tiny Winnipeg so it was just the generic Winnipeg Arena.”

In that year of transition, Burke turned to 1978 No. 1 overall pick Bobby Smith to gather intelligence. Smith had retired in 1993 after a storied 15-year NHL career that saw him play in four Stanley Cup finals and 184 playoff games (33rd all-time), while earning a Calder Trophy in 1979, and a Stanley Cup in 1986. He had always vowed to go back to school after his playing career. He was studying for his MBA at the University of Minnesota when he heard rumors that a Minneapolis businessman was planning to move the Jets there.

“I called Richard and he said, ‘Let’s have lunch,’” said Smith, who had played nine seasons for the North Stars, including their last before relocating to Dallas. “Many lunches later, he offered me the job (eventually as GM) and he asked me to give him an assessment of the Jets.”

With Teemu Selänne, Keith Tkachuk and Alexei Zhamnov, Smith quickly discovered that the Jets had “three A-plus forwards,” but he also liked the potential of defenseman Teppo Numminen, goalie Nikolai Khabibulin and several other players.

On Dec. 4, the deal to move to Minneapolis fell through and Burke had to turn to Plan B.

“The commissioner said ‘Do you still want to do this?” And I said, ‘Yes, as long as it’s some place warm,’” Burke said, laughing. “He asked, ‘What do you have in mind?’ And I said, ‘I know Phoenix fairly well. Let me look into that possibility.’

“I knew that expanding potential television markets and growing hockey in what was referred to as non-traditional markets was a serious interest of the league. This presented one of the first opportunities without the benefit of expansion, which is where a lot of the rest of it came from.”

Phoenix did not have a suitable NHL arena. Aging Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum had the same issues as Winnipeg Arena, and America West Arena had not been built with hockey in mind, so the ice surface could not fit neatly inside its bowl. Even so, the Burke family felt that it offered more potential than Winnipeg.

“From what I had heard, I think (then-Suns owner) Mr. (Jerry) Colangelo asked Gary Bettman several times if there was any reason to build this building where it could be used for another sport, notably hockey,” said Taylor Burke, Richard’s son, who served as the team’s assistant GM. “At that stage, it just wasn’t in the cards, but the sports owner dynamics were a little different back then.

“The average salary back then I think was around $600,000. The average league payroll was about $17 million. The dynamics still worked to have two tenants in the same building at that stage. That's what led to us coming to town and sitting down with the Colangelos to see if there was a deal to carve out as a tenant at America West Arena.”

With their fate decided, the Jets held a rally to say goodbye to their team and about 15,000 fans gathered at Winnipeg Arena. The Jets' logo and veteran Thomas Steen's No. 25 were raised to the rafters. Famed broadcaster Don Cherry made an appearance, and each player was introduced as he skated onto the ice amid cheers.

"Wherever this team ends up, and when this team wins the Stanley Cup, let's take it back to Winnipeg!" forward Ed Olczyk shouted to a screaming crowd.

“It was obviously a very emotional time for a lot of people,” added Olczyk, who was about to become a free agent, but hoped to re-sign with the team in Phoenix, a city where several of his family members had already purchased homes. “You become a part of the fabric of the community and I couldn’t ever imagine one of my favorite teams like the Blackhawks or Cubs picking up and moving. As a kid, I would have never understood it, so you know the hurt on one end and then you go and get this unbelievable welcome from another city. It was just a real wide range of emotions; a really weird experience.”

On April 28, 1996, the Jets played their final game at Winnipeg Arena, a 4-1 loss to the mighty Detroit Red Wings in Game 6 of their first-round playoff series. The fans stayed long after the final buzzer to salute their departing team, and the players returned the favor.

A new home

America West Arena was a unique venue for NHL hockey. Because it was built solely for the Suns, it was (and is) small, intimate, loud and ill-designed for a 200-feet by 85-feet ice sheet. The north end of the arena could not accommodate anything more than makeshift metal bleachers under the first balcony, and that balcony hung right to the edge of the glass at the north end, preventing anyone but the first row of fans from seeing the goal below them.

To alleviate the latter problem, the team hung a large screen from the rafters so that fans in the balconies could see the action in the north zone. In those days — before Brittanie Cecil died when a puck struck her in the left temple at Nationwide Arena in Columbus, Ohio, on March 16, 2002 — there were no nets to protect fans. It was especially notable in that north end.

One of my first assignments covering the team for the old East Valley Tribune was to interview fans in that section. I spoke to one man who was wearing a cowboy hat and a baseball mitt. I asked him, “Have you ever been to an NHL game?” His response: “Nope, but I’m going to catch me a puck.” Fortunately, he survived that night.

“It was a shooting gallery up there and I remember people being led out of there, not looking very good,” said Jerry Brown, the Tribune’s Coyotes beat writer at the time. “Their first move was always toward the puck and by the time they realized that was not the move you wanted to make, it was too late.”

Despite the layout, the players enjoyed playing in the atmosphere-charged arena, and they enjoyed some of the unexpected joys of sharing a venue with the Suns, whose practice court was near the Coyotes dressing room.

“I pretty much became the shootaround partner for Steve Nash because they were right up the hall and of course he was Canadian so he was probably in our room more than their room,” King said. “We’d jump on the court with them, Nash would shoot from everywhere on the court and we’d grab the ball and fire it back to him. It was so cool to interact with them. We had never been around basketball players before.

“Nash was a huge hockey fan and he dragged some of his teammates into it. I remember getting cut under the eye one day in practice and I came into our medical trainer and I laid down to get stitched up and the Suns players were in there looking at me like ‘Oh, geez. That looks really bad.’ I get stitched up and I get up and they're like, ‘Where are you going?’ I said, ‘I’m going back to practice,’ and they looked at me like I was nuts. They didn’t understand the mentality of these crazy hockey players.”

While America West Arena was far from an ideal home, it was a palace in comparison to the facilities that the Coyotes used for practices and weight training.

“There are 365 days in a year and only 41 home games,” Smith said. “It’s practicing and having a gym and a video room that really are more important in a lot of ways than the home arena. We didn’t have any of those things.”

For the first couple of seasons before the Ice Den was built in Scottsdale, the Coyotes practiced a little bit at the Coliseum, and more often at Oceanside Ice Arena in Tempe, where the NHL’s ice gurus noticed a significant problem.

“Someone came in from the league to help them figure out what they could do to get the ice sheet in better condition than it was so they were less likely to have injuries,” Richard Burke said. “The league official asked, ‘When was the last time you took the ice down?’ I think they said, ‘Six or seven years ago.’ The consequence of that was that over time, the ice had built up toward the edges so that the ice sheet wasn’t level. As we all know now, you have to take the ice out all the time.”

That wasn’t the only issue.

“I remember we shot a puck right through the glass at one point,” Doan said of Oceanside. “The glass didn’t even break. It wasn't real plexiglass. I think it was plastic. We were all standing around looking at the hole like, ‘Uh, I don’t think that's going to work.’”

Oceanside’s pothole-filled parking lot also became the Coyotes’ makeshift gym.

“We did our workouts outside in the parking lot and it was exactly the same pothole parking lot it is now,” Doan said, laughing. “Bobby Corkum would drive his truck over and play music out of the back of his truck and everybody would bring their own weights, their own dumbbells.”

Because they didn’t have a dressing room at Oceanside, the Coyotes would suit up at America West Arena and then drive their expensive cars 15 minutes to Oceanside, dressed in their equipment.

“I can't even imagine how many people saw me or Keith Tkachuk or Teppo Numminen driving with our helmets on, which you would do a lot of times so didn't have to carry it,” forward Jeremy Roenick said. “I‘m sure there were a lot of people laughing at us but it was fun; all part of the experience.”

Selling the game

About two months before the Jets played their final game in Winnipeg, coach Terry Simpson pulled Teemu Selänne off the ice to take a phone call in the coach’s office. The Anaheim Mighty Ducks had traded forward Chad Kilger, defenseman Oleg Tverdovsky, and a 1996 third-round pick to Winnipeg in exchange for Selänne, forward Marc Chouinard and a fourth-round pick. Selänne was so upset about the trade that he left Winnipeg Arena without speaking to anyone.

I asked Selänne about the trade while he was still playing and he recounted how Burke had told him not to worry; that he would be a part of the franchise’s future.

"He didn't have to call me so I thought that was nice that he called and I was happy because I didn't want to get traded," he said. “When it happened, I was just confused. I didn’t know what was going on. It was just a very sad day for me because I loved playing for them.”

Selänne had suffered some injuries and there was some question about his future durability, but he finished with 40 goals and 108 points that season, he put up 109 in his first full season in Anaheim (the Coyotes’ first in Arizona), he had set an NHL rookie goal-scoring record with 76 in 1992-93, and he was universally loved.

“The one thing I learned over the years is it’s hard to overestimate the importance of character and Teemu is one of the highest quality human beings to walk this earth that I have met,” Taylor Burke said. “He did amazing things for the Ducks subsequently and in hindsight, seeing the person he was and the talent he was, we shouldn't be surprised.”

“That one’s on me,” added Richard Burke of the trade. “My contribution to that was I said yes to a deal that was intended to get the team more defense, which was somewhat lacking. So I said to yes to that deal, which in hindsight, and in every respect was a really dumb move. I’ll leave it at that.”

Soon after the Selänne trade, Burke was looking for a face to market the game in Arizona, and the Chicago Blackhawks were looking to trade star center Jeremy Roenick with rumors of a five-year, $25-million offer sheet (big money at the time) coming from the New York Islanders.

The Hawks traded Roenick to the Coyotes in August and he instantly became the marketing tool that Burke was seeking.

“He was an absolute owner’s delight,” Burke said. “Whatever the expectation was, Jeremy was there. When we did our annual charity event, we had a tent set up for players to sign autographs. It was hot, probably 90 degrees and there were lines of fans outside and Jeremy would not leave as long as there was anybody there.”

Roenick knew that he had been acquired just as much for his marketability as for his game, which had produced two 50-plus goal seasons, and three seasons of more than 100 points while he was in Chicago.

“For sure, I think that was one of the main reasons for the trade was to make sure they got somebody who could get along and relate to the fans and was exciting to watch; somebody who would talk to and engage with fans and do the grunt work of going to events from building youth programs to charity work, whatever it was,” Roenick said. “They wanted to entice people to the game and actually, I think it was a match made in heaven because I love the fans.

“One of my favorite things about being a professional athlete was my interactions with the fans. I always had time for them. I always stopped to sign autographs for them. I always made sure that I acknowledged them and showed that I appreciated their support and that they spent their hard-earned money to come watch us play a game. I still crave that interaction today, all these years after retiring.”

While Tkachuk captured fans’ hearts with his fiery leadership and playing style, Roenick captured the Valley with his charm. His nickname was Styles, but local media altered his initials from J.R. to P.R.

“He’s American and that helped, plus he was a center and he was incredibly fun to watch,” Nairn said. “He was tough and physical but also so skilled. You couldn’t think of a better person to market the game in the league. Keith was tremendous with the media, too. He had a different style but he loved the attention. So for me, we had star power and it was great.”

About the only problem Burke had with Roenick was something he discovered shortly after the two found out that they were next-door neighbors in Paradise Valley.

“Every time Jeremy would go out his front door on his motorcycle, I would call his agent (Neil Abbott),” Burke said laughing, noting that Roenick did not have motorcycle approval in his contract.

As much as he regrets the Selänne trade, Burke considers acquiring Roenick his best move as owner. He just wishes he had kept them both and watched the possibilities play out.

“Tverdosvky was the second pick in the draft (in 1994) and Kilger was the fourth (in 1995) so on the surface it was a trade that made some sense,” Smith said. “But you have to go all the way back to Sam Pollock’s old adage from 50, 60 years ago that still rings true today. The team that gets the best player is the team that wins the trade, and clearly Selänne was the best player.

“By the same token, however, Roenick was clearly the best player in the next deal.”

While Roenick was doing the heavy marketing lifting, the other players were also doing their part. The Coyotes made numerous community appearances to connect with fans, encourage kids to play and teach the game to a market that had some hockey familiarity from the Roadrunners and its glut of snowbirds, but still needed educating.

“I remember doing a bunch of those Hockey 101 sessions with other guys in town,” King said. “We were teaching everything. ‘This is offside. This is icing.’ They did a good job trying to connect. They would put us in certain places, people would show up and ask questions and we’d talk a little hockey.

“I think it was Teppo, myself and Dave Manson at the Hard Rock (Cafe) when they were unveiling the new jerseys with Alice Cooper. We had roller blades on and we’re standing there on a stage and he told us he loved to play golf and would take us out. He took us to his club and took all our money. All my buddies back home were losing their minds. Here I am, standing arm and arm with Alice Cooper.”

The Coyotes’ Kachina jerseys were a hit with most (King said the neck collar was too rough and gave him burns in all of his fights), but the team’s brand of hockey did its own selling. Phoenix finished third in the Central Division behind Dallas and eventual Cup champ Detroit, but finished 11th in goal scoring with 240, led by Tkachuk’s 52 goals.

The team also carried more than its share of toughness, with Tkachuk, Jim McKenzie, King and Dave Manson (known affectionately as Charlie) all tallying more than 160 penalty minutes that first season.

“I remember the very first practice there was a guy named Mel Angelstad who was trying to make the team on a PTO,” Brown said. “He picked a fight with Dave Manson. Mel pulled off his clothes, rolled up his sleeves, got ready to go, looked straight at Dave and Dave hit him with one punch and dropped him like a sack of cement and that was it for Mel. That was the last we saw of him.”

During a 1992 fight with Sergio Momesso, Manson was punched directly in the throat, permanently damaging his vocal cords so he could barely talk. After dropping Angelstad, Manson barked out one word in an otherwise silent arena: “Next!”

So close, so far

When the first official Whiteout arrived in Phoenix on April 20, the fifth-seeded Coyotes were already trailing the Mighty Ducks, two games to none, but Phoenix won the next three games, including two games at home and a convincing 5-2 win in Game 5 in Anaheim to set up a potential series-clinching game at America West Arena.

That’s when the Coyotes run of first-round failures began, but what few remember are how frequently significant injuries (Roenick twice, Tkachuk and later, Doan) played a role in those losses. In Game 6 against the Ducks, Roenick suffered a knee injury and was lost for the series. The Coyotes had rallied to tie the game late and the Ducks appeared to be on fumes, but the only guy the Coyotes had who could cover speedy Ducks forward Paul Kariya was now out of the game.

At 7:29 of overtime, Selänne stuck a dagger in his old team with a ridiculous, three-zone loft pass to Kariya, who beat Khabibulin with a shot off the far post to send the Ducks back to Anaheim, where they won Game 7, 3-0, and advanced.

It’s impossible to say how much a playoff series win might have cemented the Coyotes in the Valley’s collective heart in those early years. The Suns were in decline with the departure of Charles Barkley, the Diamondbacks had not yet arrived and the Cardinals were awful but for one playoff appearance in 1998.

Maybe a series win against Anaheim would have helped grow the fan base beyond the diehards. Maybe a Game 7 win against St. Louis two years later would have helped secure the new arena that Burke was seeking in south Scottsdale, and prevented the team from making its ill-fated westward move.

“It certainly wouldn’t have hurt,” Smith said. “The playoffs are where franchises get lit on fire. I played on a lot of good teams that had a lot of success. I played in the finals four times. The list of guys who have played more playoff games than me is not very long and you just feel the excitement in the entire city whe you get on a playoff run. A win in either of those series, Anaheim or St. Louis, could have changed the entire complexion of the sporting landscape in the Valley.”

With the Scottsdale City Council wavering and property owner Steve Ellman mulling an offer from the City of Glendale, Burke gave in to financial reality.

“We had a pretty complete deal to build a new stadium at Los Arcos. The stadium deal was there. The state and local tax revenue were there and I was prepared to put up the difference,” he said. “The piece of property was owned by someone else and it came down to the fact that those people wanted to own the team as well as build the building. In the interest of getting it done, I put it straightforwardly: Either you sell me the land or I’ll sell you the team but we have to put two together so we can get this done.

“It's too bad with hindsight. If it had stayed on the east side, I guess we’d probably still own the team but going where it did, it was not in the cards. I was forthright with them in saying that my personal opinion was I didn’t think it would work out there. You need to stay over here. It didn't happen and I think all that followed was just a consequence of the economics because it wasn't working financially, it created ownership instability regularly because of the losses in trying to find someone capable of handling those losses at the magnitude they were. A followed B.”

Nobody has done more to keep the Coyotes in Arizona than Bettman. He spearheaded the NHL’s effort to seize the team from owner Jerry Moyes, who put the team in bankruptcy in 2009 in an effort to sell it to Canadian billionaire Jim Balsillie and move it to Hamilton, Ontario. He oversaw the sale of the team to IceArizona in 2013, again warding off the specter of relocation. He has endured all sorts of financial losses and off-ice issues with ensuing ownership groups and yet, he remains steadfast in his belief that the Coyotes belong in Arizona.

“Just because there are challenges doesn't mean you throw up your hands and walk away,” Bettman said. “The goal is to meet the challenges and overcome them. At the end of the day, the criticism is generally more pronounced than the reality and that’s been the case here.”

Bettman shrugs off any criticism directed his way.

“The criticism generally came from places that didn't have a franchise and would like one,” he said. “We stand by all of our communities and we do everything in our power not to relocate.

“There was criticism in a couple places where we couldn't make it work and ended up moving, including one of which resulted in the team in Arizona, so you get criticized when you stand by your franchises and don’t allow a move and you get criticized when you move them. To me, it's not about the criticism. It’s really about making sure we’re trying to do the right things. I am comfortable that in the course of the last 25 years, we and the ownership groups for the most part have tried to do what they thought was right.”

Bettman knows that the Coyotes still face financial challenges in Glendale. Under Meruelo and president Xavier Gutierrez, they are still seeking a permanent arena solution with the East Valley a likely target.

“The vision a decade ago or so was that the greater Phoenix area was going to continue to move west and at some point Glendale was going to be the center of it,” Bettman said. “That reality didn’t happen and that has had an impact on the team's ability to really engage its fans on a more regular basis in terms of attending games. Depending on where you are in the Valley, we know how long it can take to get to the arena.

“The good news is I think they are in a terrific place and Alex Meruelo has the commitment and the resources to ultimately get this franchise to a place where everybody will be thrilled. These things don’t happen overnight and there’s always a learning curve for new ownership, but I’m very excited about the future prospects of this club.”

It’s also important to note the Coyotes’ impact on the community, Doan said.

“Twenty-five years is a long time and there’s something to be said for that, mostly that we have influenced hockey in the Valley,” he said. “Look at (Scottsdale product) Auston Matthews or how many different guys have been born here and played minor hockey that are starting to have an impact on the NHL and the hockey world. Phoenix is having an impact and the roots are running a little deeper and creating a little more stability and that’s the most exciting part. It has taken a while to get a root system in place, and hopefully we keep going and doing it the right way.”

As director of player recruitment for the St. Louis Blues, Tkachuk can’t keep tabs on the Coyotes as closely as he did while he was here. But he still takes pride in the role he played as the team’s first captain in establishing the Coyotes in Arizona.

“A lot of people were expecting that thing to fail, but I'm glad it hasn’t,” he said. “There have been a lot of different owners and that doesn’t bode well for the success of a franchise because you need stability and consistency. But I'm glad NHL hockey is in Arizona, and there’s no doubt in my mind that if the arena were in the right place, more fans would come back and it would work. I know because I have seen it work.”

Follow Craig Morgan on Twitter: @CraigSMorgan

Nice work, Craig. I spent years covering New York team visits to America West as a reporter, and I spent a LOT of time at Sky Harbor coming to and going from the bankruptcy hearings and City Council meetings while I was with the League. The Coyotes are a special story and you told it very well. Cheers.

Great piece. Only missing the Ken Burns narration.

I'm sort of happy that people here have picked up on the "boo Bettman every time" thing simply because it's fun and I think he might be disappointed if he didn't get the wrestling heel reaction he's used to. HOWEVER, if anybody ever raises the cup at our arena we ought to be the one place where he gets applause instead.